T

Kollwitz: "Sharpening the Scythe"

_________________________

(originally Published in the Santa Barbara News and Review: 4/8/77)

Imprinting Human Sorrow, Etchings Profoundly Political

T

Kollwitz:

"Sharpening the Scythe"

_________________________

(originally Published in the Santa Barbara News and Review: 4/8/77)

By Dan Gheno

To the European painters of the 19th century, America was a rude, artless land. Certainly America produced successful painters during this period, but these people (Whistler, Sargent, Cassatt et al) were all expatriates. They had rejected the transient, cowboy individualism of the US and they painted in European-inspired traditions.

Europe’s cultural dominance, which was continuous for 2000 years, seemed to evaporate overnight between the two world wars. "20th Century European Prints," the current show on the balcony of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, displays the continent at its aesthetic apex, just before fascism depleted or imprisoned its stock.

Many of the artists represented here, like Oskar Kokoschka and Lyonel Feininger, fled to England and America. Others, like Max Beckman and Emil Nolde, remained but were forbidden to paint. Some, like Ernst Kirchner, committed suicide, while Kathe Kollwitz died slowly and painfully under the mistreatment of fascism.

During this time the artists who were forbidden to paint simply switched from smelly oil paints to scentless watercolor paints. But the printmakers had a more difficult time, since their machines were bulky and their inks had a pungent smell, which, like oil paints, would instantly betray them to the Nazis.

KOLLWITZ

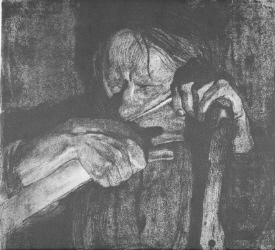

Although Kollwitz continued to work during the war, her sorrow for humanity was unparalleled by other artists. Her lithograph, "Seated Woman with Upraised Hand," poignantly describes her anguish and concern. She portrays the seated woman with a fixed, unflinching gaze, and she renders her body with tense, rough strokes. A voidlike background seems to isolate and engulf the figure with its intensity and uniformity.

This isolation is little different from the feeling of helplessness she felt after her son and husband died. Since she was widely known and loved for her prints that championed the cause of the hungry workers and the destitute farmers, the Nazis could not further her isolation by forbidding her to work.

So they did something much worse. Exploiting her reputation, they pirated her socialist prints, and republished them as posters with Nazi slogans.

PICASSO

Picasso, another printmaker reputed for his political activism, is represented by an etching called "The Frugal Meal." Although this print, depicting an emaciated couple at their barren dinner table, was only the second one he did in his long career, many people consider it his magnum opus. It’s a profoundly somber composition, with a velvety web of black shadows closing in and embracing the couple. As in Kollwitz’s prints, the couple meet their plight with mocking stares of indifference.

Unlike Picasso’s later, more clinical works, this etching seethes with emotion and artistic struggle. At the time he made this print, he was too poor to buy a new etching plate, so he salvaged one which already had a landscape engraved into it. Like Rembrandt, who also followed the same tactics, Picasso diligently worked and re-worked his image until the landscape vanished underneath.

In contrast to this violently textured print from 1904, Picasso is also represented by a sensitively quiet etching, "Au Repos," done a year later. Picasso was a multi-faceted man, continuously changing motifs with little regard for "tradition" or "school of thought."

A study of Europe’s last gasp would not be complete unless it were compared to the works of American artists of the same era. "American Artists: Views from Home and Abroad" (showing concurrently with the European print show) offers this opportunity.

Among the American artists who are represented here —Stella, Pennell, Church, Dole and Parshall — the life of Georgia O’Keefe seems best to typify the tug-of-war that tore these artists between their homeland and Europe’s ideals.

Around the same time That Picasso was shedding European traditions and precepts, Georgia O’Keefe was trying to emulate them. It wasn’t until much later— near her thirtieth birthday —that she finally decided her work was too "derivative." She burned all of her work, and began anew, like a Phoenix rising from the ashes of her old paintings.

She now uses her immediate environment for inspiration, finding greatest stimulation in the desert where she did "Dead Cottonwood Tree." Her picture is totally devoid of texture. It’s flat and is painted with pale pastel colors. But this doesn’t mean the painting is weak. O’Keefe demonstrates that silence and restraint are sometimes more powerful and refreshing than the sock in the jaw, which is often offered by other American artists like George Bellows.

Most people remember Bellows for his savage renditions of the boxing world. Like America of the late l9th Century, which was experiencing the birth pains of industrialization, his paintings brim with hubbub and clamor.

However, when you visit this show, don’t be surprised that this is not the side of Bellows you will see. You will face a snowscape and a seascape, glowing with clear air and thick, clean paint. The colors are resplendent, quite unlike his boxing paintings and bustling cityscapes which seem to be painted with grime and soot.

George Bellows’ rough-and-tumble America hit its peak in the twenties, and collapsed with the Great Depression. But while the Nazis continued to intimidate artists in Europe, the WPA art programs helped American artists get back on their feet. As a result, multitudes of young people and destitute immigrants were able to launch themselves into art careers. Most of these people were untutored in European-derived styles, so they brought a new freshness to the art world.

By the middle of World War II, when the WPA program ended, many of the artists had grown into "sophistication," and they created the backbone for the Eastern art establishment which thrust America into the artistic prominence Europe once held.

In retrospect, it seems silly to divide artists into continent classifications. After all, art is a universal concern that cannot be contained by geographic boundaries. The only boundaries are the limits of human imagination.

| REVIEW #7 | REVIEW #8 | REVIEW #9 | REVIEW # 10 | |

| REVIEW #12 | REVIEW #13 | REVIEW #14 | REVIEW #15 | |